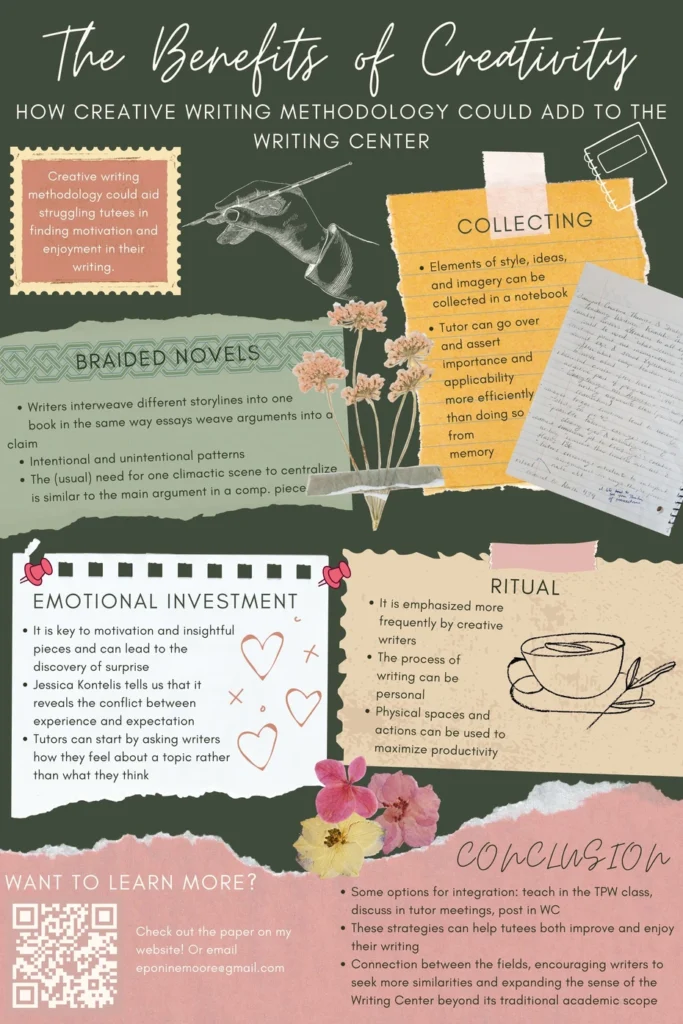

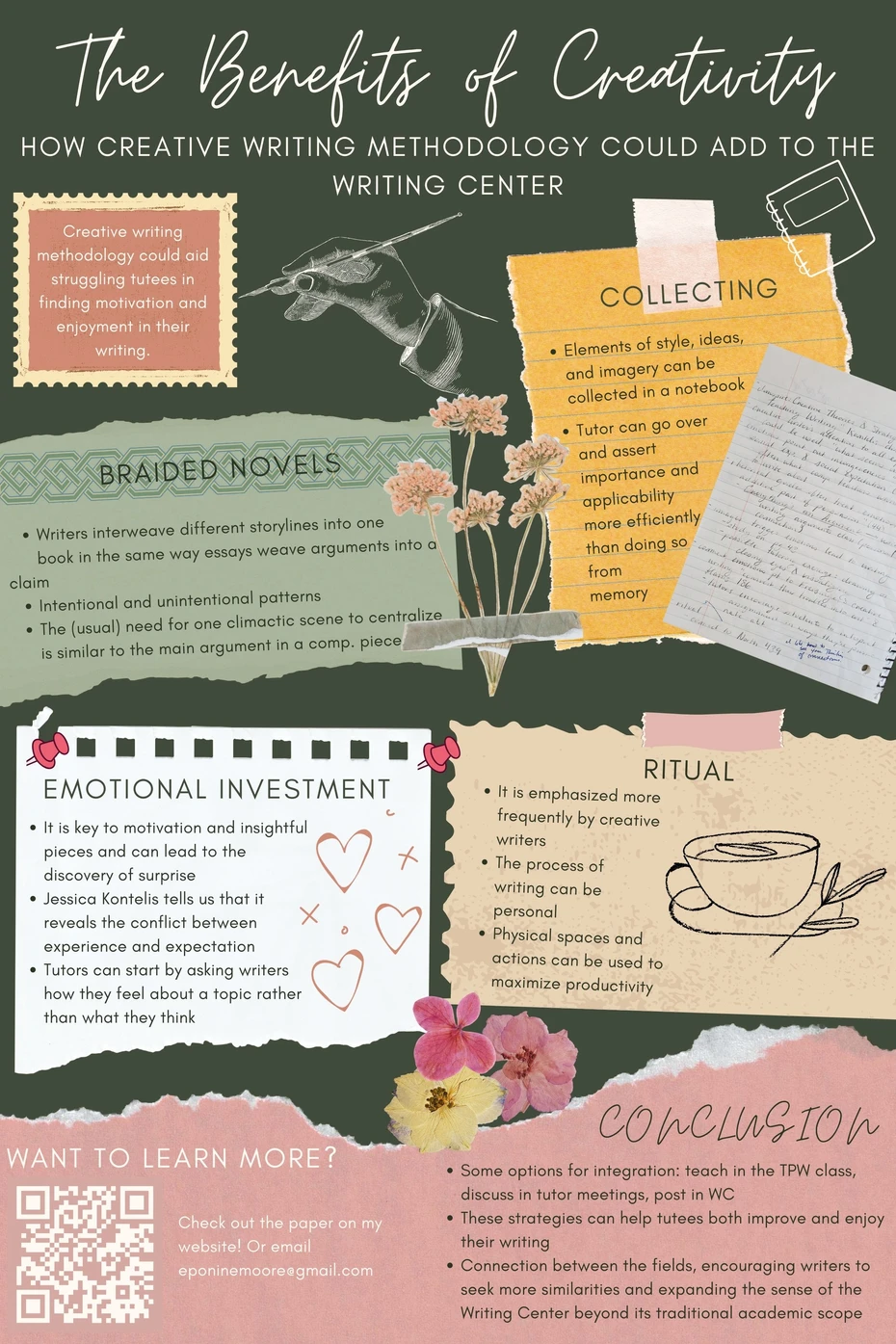

How Creative Writing Methodology Could Add to the Writing Center

Introduction

As a Public and Professional Writing major and Nonfiction minor, I tend to walk the line between creative and academic writing more often than not. Learning both at the same time has made me come to realize how similar the two are, and how superficial the distinction between them often is. There’s a lot to be gained from the other on either side.

Mara Wagnon, a senior Rhetoric and Writing undergraduate at the University of Texas in Austin, who’s both a Writing Center consultant and copyeditor for the database Praxis, claims that “the writing center is, however intentionally, presented as a space for academic writing” (“Bring Me Your Darlings”), which, from my experience so far in this course, seems to be true at least at the University of Pittsburgh. Because of this, I was interested in seeing how the WC could benefit from a more creative touch. One advantage I predict is an increase in writer investment, as the ability to approach academic writing creatively is often what keeps me motivated for assignments that I’m at first uninterested in, and key to my success in many classes. Writing Center scholars have spent decades finding and creating strategies to aid their tutors and writers, but creative writing methodology lacks a significant amount of exploration in this field, and it could be an incredibly helpful tool especially in encouraging unmotivated writers work on academic topics.

Preexisting Similarities

Core Similarities: Student-Centeredness, Asking Questions, and Peer Audience

There are many preexisting similarities between WC philosophy and creative writing discipline. In his “Writing Off the Subject,” Richard Hugo, a prolific poet in the 20th century who taught at University of Montana in Missoula (“Richard Hugo”), stated: “I hope I don’t teach you how to write but how to teach yourself how to write” (“Poetry in the Classroom” 1) regarding his work as a professor of creative writing classes. His ideology is similar to that which governs the WC, where the tutor’s “primary object in the writing center session is not the paper, but the student” (“Minimalist Tutoring” 1), according to Jeff Brooks, author at Seattle Pacific University. Each work is the writer’s piece, and tutoring is not writing or editing, but aiding the writer as they learn how to write.

Randall R. Freisinger, Assistant Professor at Michigan Technological University and director of the Missouri Writing Project, argues for a more creative approach to composition classes, including the strategy of asking students questions (“Creative Writing and Creative Composition” 284), which is one of the very same strategies that Brooks suggests for advanced minimalist tutoring (“Minimalist Tutoring” 3). Similarly to Hugo, Freisinger also argues for the interpretation of composition courses as “student-centered and writing-centered,” and attempts to instill a sense of peer audience within his classes (“Creative Writing and Creative Composition” 285).

Because many students come to the Writing Center voluntarily we can assume that, as Stephen North, Writing Center director at SUNY Albany, asserts, “nearly everyone who writes likes–and needs–to talk about his or her writing (“The Idea of a Writing Center” 439, 440). This desire for writing discussion automatically puts writers on a more equal footing with their tutors. Not to mention, the existence of peer tutors and the purposeful student-focused methodology that even professor-tutors employ are key efforts for that same feeling.

All of these similarities between WC and creative writing methodology go to show the inherent likeness between the practices of these two fields. Because they are already so connected, it follows that further cohesion of interdisciplinary strategy would likely benefit them both, in methods which they already share, and completely new ones. Not only that, but acknowledging their resemblance could both legitimize the field of creative writing in a culture which sometimes views it as unprofessional, and broaden the scope of the WC beyond its primary focus on academics.

What to Focus On: Surprise and Brainstorming

In “Portrait of the Tutor as an Artist: Lessons No One Can Teach,” Steve Sherwood, director of William L. Adams Center for Writing at TCU, interpreted tutoring as an art form, and outlined four vital aspects of the tutoring process which are also elements of artistry. These include, most importantly for our purposes, “surprise” (53). Surprise in the writing process exists in seemingly unfounded realizations, or hopping from idea to idea. The dissection of this inherently creative experience–finding the trail between ideas–is what leads to the development of pieces (57). For example, one semester Sherwood observed a writer stuck in the middle of an essay about invention processes, when the tutor asked “‘Why do so many people come up with great ideas in the shower?’” The writer responded, “‘Steam,’” and after a laugh, the two “drew a cause and effect chain leading from steam to heat, from heat to relaxation, from relaxation to revelation, and from revelation to invention” (56).

It’s the tutor’s job to both encourage the discussion which leads to these revelations, and assert the importance of the writer’s subconscious logic, which they often initially dismiss as inadequate. As assistant professor of English at George Washington University, Judith Harris, claims, “by utilizing access to the unconscious, a writer can discover a fund of material he or she wouldn’t have ordinarily been aware of” (“Re-Writing the Subject 200). These jumps of thought are key to the creation of influential pieces, and they are a foundational part of the tutoring experience that many tutor’s know, but don’t particularly examine.

These theories suggest that a combination of a writer’s personal intuition, or unconscious thought, with a specific set of circumstances is what leads to truly distinctive products, and what makes writing and art so unique. This process is part of the core of creation, and the key to crafting revolutionary work. The writer works on the art of dissecting surprise with the help of the tutor, and their questions, in order to create a solid narrative for the piece.

The idea of surprise is also apparent in Hugo’s work, where he advised “don’t be afraid to jump ahead… it is impossible to write meaningless sequences” (“Poetry in the Classroom” 1). Hugo focused on poetry, and so his opinion on meaningless sequences is that there is always an undercurrent of subconscious thought beneath whatever comes out on the page. Whether the writer knows it or not, there’s a reason they thought of the next idea, and a way to connect or build off of it within their work. While, in academic writing, more explanation is needed than what poetry requires, the idea of trusting the subconscious mind–following it’s seemingly circuitous routes and dissecting the leaps in logic–is all part of the process of writing, and facilitating it is a huge part of the tutor’s role.

One of Hugo’s ideas, using words for the sake of sound, might draw controversy as a strategy within the WC, but it has a lot of potential. In essence, it’s similar to the idea of brainstorming. Writers are often taught throughout middle and high school to create outlines, putting their entire piece together before even beginning to write it. In reality, this is often more difficult than simply putting pen to paper and allowing one’s thought process to proceed on the page, thus saving revisions for later. While Hugo might have been more focused on the melodic cadence aspect of poetry writing than scientific word vomit, there’s no harm in pursuing that syntactic quality while brainstorming for academic papers, especially if it aids the student in their motivation to keep writing. Not to mention, almost every writing style has some sort of rhythmic flow, even traditional academic dialect, and following that current allows a route for the outpouring of ideas that the writer can later refine.

Both of these ideas, surprise and writing for the sake of sound, can be put into practice both with candid discussion of the writer’s topic and ideas, or timed free-write exercises during tutoring sessions. Though these are already used by many tutors, especially discussion, acknowledging the fact that getting seemingly off-track can lead to revelation could be incredibly important in the writing center. Not only that, but other exercises can be drawn from these processes, some of which are illustrated later. Because these strategies’ foundations are already supported by both creative and WC writing practices, their applicability within a tutoring session is already substantiated.

New Strategies from Creative Writing

Images

There are also aspects of creative writing methodology that tutors don’t generally pursue, at least in their philosophy if not in practice. Jessica Renay Kontelis, in her dissertation paper for a Doctorate of Philosophy, claims that another key aspect of the creative process is the use of images. According to a study of 148 students at Midwestern University, “over a quarter of participants used images in their thought processes to recall information, work through abstract ideas, and motivate their writing” (“Inspire” 43). These students also found that the images were emotionally laden, and that those emotions lead to th direction their piece ended up taking. This introduces a potential exercise tutors could do with their writers, where the tutor asks the writer to brainstorm images related to their topic and describe it, and the tutor takes notes.

Though I’ve never experienced an example of this in the WC, I did go through this exercise on my own for a recent essay I wrote about prison reform. A section of the piece regarded the opposing side of my argument: those advocating longer sentences and harsher conditions for the incarcerated. In order to understand this perspective, I tried to envision, based on memories, the moments in which I had been frightened by crimes reported on television. I imagined gruesome security camera footage, a somber reporter, and the silent blank faces of my family around me as we took it all in. This visualization process brought forward emotions, counterarguments for my paper, and it helped me understand the reasoning behind my opponents stance.

Drawing

Some tutors use drawing as a way to illustrate suggestions, structures, or ideas for their writers, but Sarah Leavitt, the Assistant Professor of Graphic forms at the University of British Columbia and another contributor to A to Z of Creative Methods, goes beyond this strategy. A comic artist and writer herself, Leavitt has her writers drawing “in every session of [her] comic classes – not only to create finished comics, but to discover and explore stories in the conception and planning stages” (53). This process could be more helpful than discussion based techniques for writers who process better visually than vocally or audibly.

Leavitt sometimes asks her students to “think about a childhood memory and make rough sketches of what happened,” claiming that “the act of drawing often unearths memories of events or details that haven’t emerged in written explanation” (53). Not only could visual learners use this process, but those writers who are tentative to voice their ideas in conversation might find it easier to illustrate them, or perhaps participate in an illustration started by the tutor, therefore facilitating easier discussion and, eventually, an even more encompassing product. This process on its own could also be a great brainstorming strategy, especially regarding narrative essays, which are often assigned in composition classes.

Collecting

Another writer in A to Z of Creative Writing Methods, is Ander Monson, an English professor at University of Arizona, who emphasizes the importance of “collecting” in creative writing (43). He suggests, when it comes to writer’s block, for students not to “start from nothing… start gathering and when you turn to the page, you’ll have something to start with” (43). This process is similar to the introductory research often required before coming up with a topic or argument for a paper. However, he suggests going beyond the collection of facts or opinions, telling students to “collect trinkets and doodads, but also bits and images and ideas and strangeness and fragments of language.” This could especially be helpful for writers attempting to create a more signature style in their writing, as they could gather inspiration from the readings they already have to do.

Monson also asserts that students are “doing it [collecting] anyways. Let’s make it more formal. Start a menagerie or a journal” (43), which is almost exactly the same practice as the optional extra credit task in Tutoring Peer Writers of keeping track of research in your notebook. This could be a great exercise for writers in the WC to make sure they keep track of their insights. It would log their subconscious logic, conserving ideas that the writer might think is not good enough for the final paper, but OK to write down. The tutor can then go over these notes and assert their importance and applicability in a more effective process than the current strategy of doing so mostly from the writer’s memory. It might even be a good suggestion for writers who frequent the WC to keep a notebook for all of their writing, not just a single piece, in order to build up an accumulation of information that could pertain to style or later papers. This notebook could also help fuel writer’s confidence, as it is a physical manifestation of how much research and thinking they have done, and how far they have come.

Ritual

The idea of the ritual of writing is already apparent in WC philosophy; Stephen North cites the tutors job to “observe it” and “change it: to interfere, to get in the way, to participate in ways that will leave the ‘ritual’ itself forever altered” (“The Idea of a Writing Center” 439). Every writer has a ritual, but creative writers often emphasize a complex process through which they achieve inspiration and flow more so than academic. Instead of relying on the interpretation of writing as a “purely cognitive problem” where writers “force themselves into chairs in secluded corners, expecting that knowledge of their subjects, audiences, and the mechanics of arrangement and style will automatically produce cogent, engaging writing” (Kontelis 54), Kontelis suggests that the process of writing should be personal, often regarding specific physical spaces and actions in order to maximize productivity.

In order for tutors to help writers find a ritual that will work for them, and therefore overcome the struggles they may be facing in either getting started or keeping the flow of their work, they can utilize the exercise that Kontelis does with her students. First, the tutor and writer make two separate lists, one of rituals and one of writing blocks. Then, they pair the rituals with their blocks, “and try to invent new rituals for those creative blocks without easy solutions” (56). For example, if a writer’s specific block is finding a thesis for their topic, their ritual could be to watch youtube videos relevant to the subject in order to get a sense of context and other people’s opinions, therefore helping them find a focus before they start their writing or research.

Braided Novels

The methodologies of “braided novel” writers, or novels that interweave different story lines into one book (McKinnon 16), can easily be applied to compositional writing as well, considering the similarities between the characters of a braided novel and the arguments and evidence intertwined within an academic essay. In A to Z of Creative Writing Methods, Catherine McKinnon, a “Discipline Leader of English and Creative Writing at the University of Wollongong, Australia,” writes about the process of writing a braided novel. McKinnon “braids with intention, looking for patterns sometimes formed unintentionally” (17), which is reminiscent of the tutor’s job in helping writers recognize the connections and patterns in their writing. Also, her opinion that novels need “one climactic scene to operate as the narrative’s moral heart (2010)” (18), is very similar to the function of a main argument in a compositional piece.

One of McKinnon’s strategies in writing braided novels is to write down all of her different plot points, then use different colored pens to draw lines of connection between them, where each color coordinates with a type of connection. Processes similar to this already exist somewhat in the WC, such as tutors jotting down notes of revelation while they and their writer discuss the paper, but this exercise of outlining every aspect of a piece and then thinking through specific types of connections could be incredibly helpful with writers struggling to work out the organization or final argument of their piece.

Another strategy McKinnon uses is to first list her characters and their qualities, “charting difference and similarity,” and then use this visual to evaluate the story function of each character and decide how they could be best introduced to the story. If a tutor replaced characters with arguments, evidence, or scenes, this would be a great strategy for writers to figure out which pieces actually contribute to their paper’s overall point, where they best function, and how to introduce them while maintaining, or even improving, the flow of their paper.

Emotional Investment

A key part of creative writing is emotional investment, which is sometimes considered unprofessional in academics, but is often crucial to a worthwhile product in both fields. Kontelis outlined the importance of emotional investment in writing beyond the creative genre, and into academic pieces. She argues that “emotions are a rhetorical analytic that point us toward relational observations about ourselves and the people around us.” Emotions are what point out incongruencies “between personal experience and social expectation” (45), which is often the point which composition professors want their students to write about. While many rhetorical guides, such as Everything’s an Argument, by Andrea A. Lunsford et al.– which is currently used in rhetoric classes at the University of Pittsburgh–treat emotion as “an additive part of persuasion” (44), Kontelis argues that it should be a much more central aspect of the writing process. This is similar to Freisinger’s point, that students enjoy creative writing because “they feel troubled and wish to convert their troubles into art” (“Creative Writing and Creative Composition” 283).

While academic prompts often host a narrower scope of topic, tutors can still ensure that students are adequately invested with their pieces by encouraging them to interpret assignments in ways that they are passionate about. For example, my Seminar in Composition class freshman year was focused on writing reviews, and one of the most narrow essay topics we received was doing a review of the movie “A Star is Born.” I personally didn’t enjoy the movie, so in order to stay invested in the paper, I focused on what I disliked most about it, which was the misogyny I saw intertwined not only in the characters, but also in the story creation. Through the frustration I had with the movie, I was able to write one of the best essays I’ve ever written. By asking writers how they feel about their topic, rather than just what they think, tutors could potentially help many writers be able to interpret prompts in ways they’re actually excited for, which is key for not only motivation, but also insightful pieces. Often when a writer is uninterested in a topic, it’s partially because they have nothing new to say about it, so finding an emotional connection can lead to the discovery of surprise.

Conclusion

These practices would well suit the arsenal of strategies already used at the WC. Simply having them taught in the TPW class, discussed in a meeting, or hung up on a poster in the WC would be enough to provide tutors different avenues with their writers. Not only that, but perhaps the fact that these are creative writing strategies will instill a sense of connection between the fields, encouraging people to seek more similarities and lose the sense of the writing center as a purely academic field.

While it’s true that I’ve encountered students who simply don’t connect with the creative aspect of writing, a slow application of these strategies could perhaps make them more amenable to the idea. And if not, then there are plenty of other methods the tutors can use to aid these writers. On the other hand, there are plenty of students who struggle with writing because they are uninterested in the topics assigned to them, so more creative methods are likely to reinvigorate their interest. The overall objective of this paper is to introduce small ways of not only aiding writers and tutors, but getting students interested in writing, or at least diminishing the dread some feel when encountering a writing assignment. By adding strategies that both ease the writing process and allow the writer more freedom and creativity, I hope that students who come to the writing center will not only improve their work, but also enjoy it.

Works Cited

A To Z of Creative Writing Methods, edited by Deborah Wardle, et al., Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2022. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://search.proquest.com/legacydocview/EBC/7075670?accountid=14709.

Brooks, Jeff. “Minimalist Tutoring: Making the Student Do All the Work.” The Writing Lab Newsletter, edited by Muriel Harris, vol. 15, no. 16, Feb. 1991, pages 1-4, https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/v15/15-6.pdf.

Freisinger, Randall R. “Creative Writing and Creative Composition.” College English, vol. 40, no. 3, 1978, pp. 283–87. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/375788?searchText=creative+writing+advice&searchUri=%2Faction%2FdoBasicSearch%3FQuery%3Dcreative%2Bwriting%2Badvice%26typeAccessWorkflow%3Dlogin&ab_segments=0%2Fbasic_search_gsv2%2Fcontrol&refreqid=fastly-default%3Affd6d0d482dcd05b95ccf2e957f7070a&typeAccessWorkflow=login&seq=1. Accessed 18 Oct. 2023.

Harris, Judith. “Re-Writing the Subject: Psychoanalytic Approaches to Creative Writing and Composition Pedagogy.” College English, vol. 64, no. 2, 2001, pp. 175–204. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1350116. Accessed 16 Nov. 2023.

Hugo, Richard. “POETRY IN THE CLASSROOM: Writing Off The Subject.” The American Poetry Review, vol. 4, no. 5, 1975, pp. 4–5. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/27775034?sid=primo&typeAccessWorkflow=login. Accessed 18 Oct. 2023.

Kontelis, Jessica R. Inspire: Creative Theories and Strategies for Teaching Writing, Texas Christian University, United States — Texas, 2018. ProQuest, http://pitt.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/inspire-creative-theories-strategies-teaching/docview/2046872926/se-2.

North, Stephen M. “The Idea of a Writing Center.” College English, vol. 46, no. 5, 1984, pp. 433–46. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/377047. Accessed 16 Nov. 2023.

“Richard Hugo.” Poetry Foundation, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/richard-hugo. Accessed 17 Nov. 2023.

Sherwood, Steve. “Portrait of the Tutor as an Artist: Lessons No One Can Teach.” The Writing Center Journal, Lerner, Neal editors et al. vol. 27, no. 1, 2007, pp. 52-65, https://www.iwcamembers.org/wcj2/27.1.pdf. Accessed 18 Oct. 2023.

Wagnon, Mara. “Bring Me Your Darlings: Creative Writing in the Writing Center.” Praxis UWC, 4 Jun. 2019, http://www.praxisuwc.com/praxis-blog/2019/5/14/bring-me-your-darlings-creative-writing-in-the-writing-center?rq=creative%20writing. Accessed 18 Oct. 2023.

Leave a Reply